I’m (almost) absolutely sure you won’t believe it: I never seek to mimic/emulate (or using a uglier word in this case: imitate, copy) photographs of great masters (of all of us photographers, I believe), but this ghost (if it’s really a ghost he’s a good one) chases me….even though, premeditatedly (this is another thing I don’t think you’ll believe), I never go out to my photo shoots with that idea in my head. But, they keep happening through the years. Here I show SEVEN examples.

Tag: portraits

[.P.O.R.T.R.A.I.T.S.]

{…portraits…always portraits…}

Brassaï (1899-1984) questions in his book ‘Proust and photography’ (original title: ‘Marcel Proust sous l’emprise de la photographie’ and published in Brazil in Portuguese in 2005 by Jorge Zahar Ed., Rio de Janeiro) (version that I now read) that “a simple photograph would possess so as much presence as a real person? Yes, Proust thinks, the photo is even a kind of real double, loaded with all the potentialities of a being”.

And Brassaï goes on to say: “every portrait would not attest to the presence of a person in front of a lens, would it not be an image traced by light itself, as its etymology indicates, by the way: photos=light, graphein=trace? WOULDN’T IT BE THE VERY EMANATION OF THE BEING?”

[dis-words]

[I am not good with words; I have for myself that I was born disfigured from that thing called the word; I need to talk about it to break the spell; it seems that I am convinced that I was born to see-hear-appreciate; with a sharper feeling; because I like to see the rooster crowing: because I like to see the birds singing: the noise of rain-on-the roof; of a shooting star streaking the sky on endless nights: the ticking of the time clock: the flashing light of the fireflies: perhaps even the rays of the sun illuminating the mornings: the warm colors of the setting sun; I hear the noise of the moon’s phase changes: of the movement of the clouds: of the twinkling of the stars in the firmament; I hear the brightness of the Milky Way in the sky on a clear night: the speech of the deaf and dumb: the silence of innocents: of tired souls; I hear the silence of the emptiness of love that is gone: of the warmth of the loving gaze of father and mother: of the silence of a fallen leaf on the floor of the branches of trees in autumn: of the blossoming of flowers in the meadows: of the heat of the animals in the bush : the dangling of the dogs’ tails: the sadness of death and grief: the footsteps of frustrated dreams and nightmares of sleepless nights: the silence of fear of the dark: the loneliness of lonely and abandoned old men: the jealousy of the unloved wife and despised; I hear the sweat running down the face of a tired worker in the midday sun: the silence of just men and women, workers, at the end of another day’s work; I hear the hope of the arrival of letters: the anxiety of a mother waiting for her child at the door of the house: the silence of tired hands, of peaceful minds and hearts: the sounds, the colors, the sensations of absence: the faith and courage of righteous men: the sound of the cool breeze of the cold April mornings]

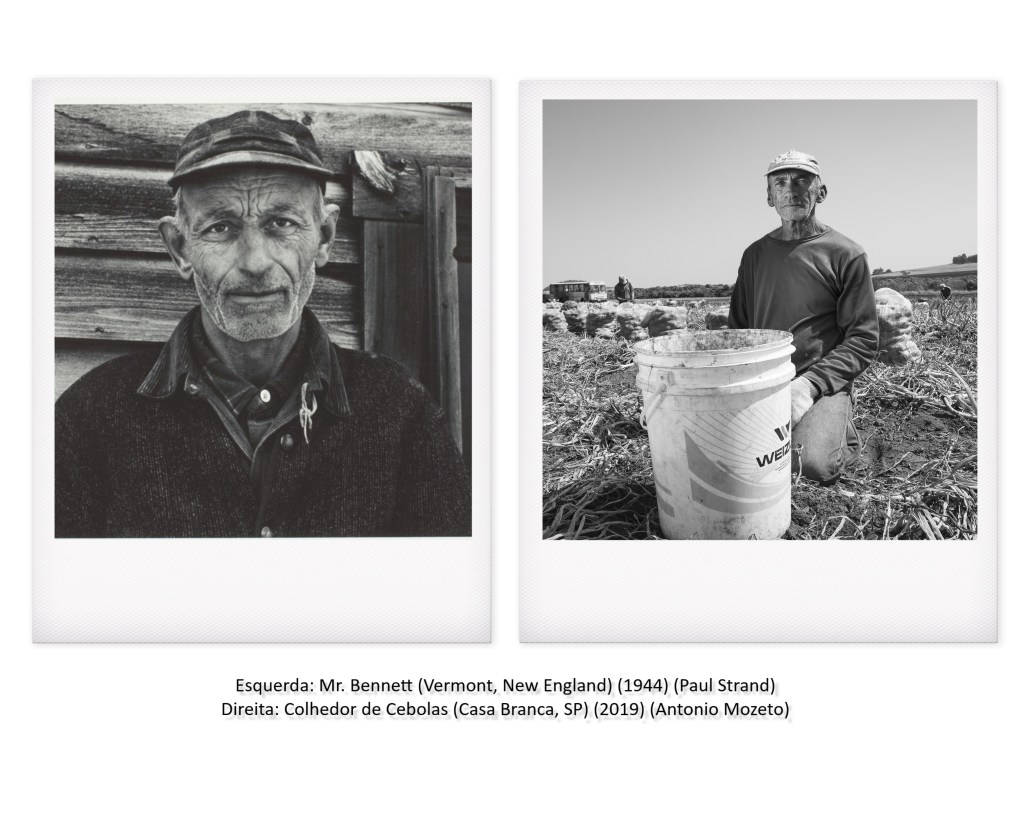

Me and Mr. Strand.

In the book “Understanding a photograph” by John Berger (organization and introduction by Geoff Dyer and translation by Paulo Geiger) (Cia das Letras. São Paulo. 2017) (an authentic treatise on photography made known by master Juan Esteves, São Paulo) I read and reread it a few times (good things have to be tasted homeopathically) the ‘reading’ of the photo on the left of 1944 (made three years before this writter was born) by Paul Strand in Vermont, New England-USA, and the that you can read there with all the letters impresses me, touches me a lot.

Berger says of Strand’s work: “His best photographs are unusually dense – not in the sense of being overloaded or obscure, but in the sense that they are filled with an unusual amount of substance per square centimeter. And all this substance becomes the essence of the object’s life. Take the famous portrait of Mr. Bennet. His jacket, his shirt, his beard on his chin, the wood of the house behind him, the air around him become, in this image, the very face of his life, of which his facial expression is the concentrated spirit”.

Right: Onion harvester (Casa Branca, SP-Brasil) (2019) Antonio Mozeto.

The photo on the right that I took in 2019 of an onion harvester in Casa Branca (SP-Brazil) has a much more explicit surface given that the worker is in his own working environment. And, without due permission, but with due boldness, ‘reading’ my photo, I make Berger’s words about the current Paul Strand photo mine: all the substance of the photo is in the expressive look of the worker, in a marked face due to the hardships of hard work and the properties of his surroundings: the harsh and striking light of the day in full sun, the onion harvesting bucket, the onion sacks lined up behind him, two companions of toil and the bus that brings him a lot early for the harvest and takes you home at the end of another day of this person’s hard daily workday.

As Berger rightly said (operate citato) “in the relationship between photography and words, the first yearns for an interpretation, and words usually supply it. The photograph, irrefutable as evidence, but weak in meaning, gains meaning from words”.

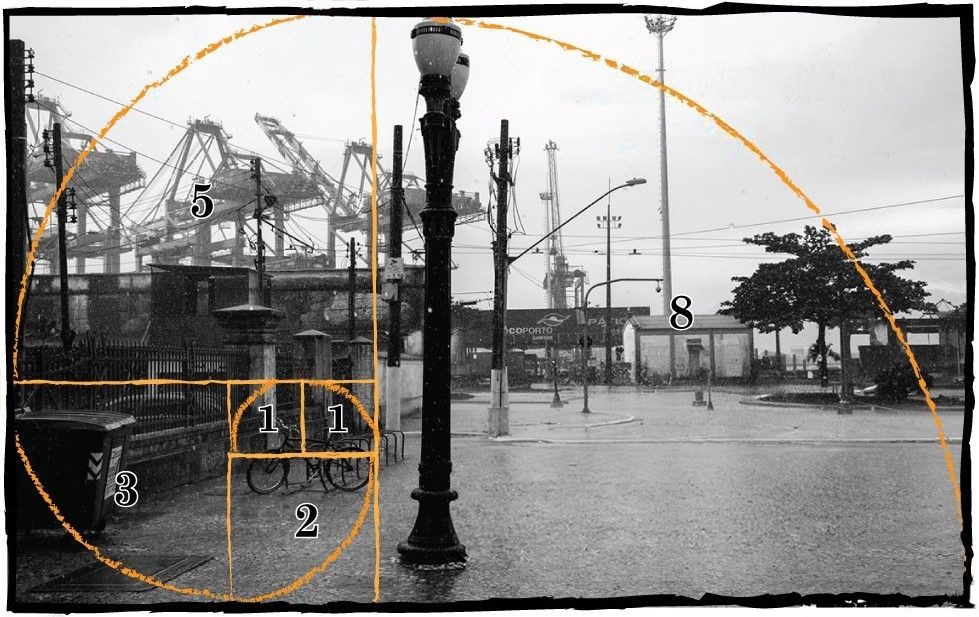

an air of mystery…

The black and white photograph for me is this: they are pictures with an air of mystery, of tension in the air. Mystery and tension suspended in the air as if in a micro second a posteriori there would be an explosion or another sudden change and everything would become different from this previous instant. For me, nothing like street photography to fill these pre-requisites.

Continue reading “an air of mystery…”

Emparelhamento palavra-fotografia (Word-photography pairing)

Inspirado num artigo escrito por Geoff Dyer chamado ‘forma: palavra + fotografia’ e publicado pela revista Zum em maio de 2014 encontrei ressonância para um aspecto de grande relevância para mim na fotografia que é ‘casamento da palavra com a fotografia’ ou da ‘fotografia com a palavra’. Para mim muitas vezes há, aí, um intercâmbio de papéis, i.e., de quem nasceu primeiro, como a história: ‘o ovo ou a galinha?’: ‘a palavra ou a fotografia?’.

Dyer cita alguns livros que historicamente encaixam-se nesta categoria e após ler seu artigo fiquei tentado em comprar um deles e acabei comprando o ‘Looking at photographs’ onde John Szarkowski ‘casa’ 100 fotografias do acervo do Museu de Arte Moderna de Nova York (as mais icônicas em sua perspectiva no ano de 1973, é lógico) com ‘palavras’ sobre tais fotos. Apesar de ter nas mãos o livro menos de 24 horas, já pude perceber verdadeiras joias – tanto ‘joias-palavras’ como ‘joias-fotografias’ – que há no mesmo.

Uma dessas preciosidades é uma foto de William Klein feita em Moscow em 1959 que o livro do Szarkowski não dá o nome (que mancada Szarkowski!), mas eu sei que é ‘bikini’ porque é capa de um Photofile (Thames & Hudson, 2017) do Klein que tenho em minha pequena biblioteca. “Bikini’ foge – no meu modesto conhecimento e entendimento da obra de Klein – da ‘regra’ das (quase totalidade) fotografias desse autor que prima por ‘meter’ dentro do retângulo grande diversidade de elementos de composição. ‘Bikini’ tem 6 camadas ou planos lindamente definidos….e, muitos mistérios…tensões…e, poesia.

Pois é: entre as várias coisas que o Szarkowski fala dessa fotografia leio algo que quero compartilhar:

“It was recognized long ago that so-called good photographic technique did not invariably make the best picture. Sometimes the gritty, graphic simplicity of the badly made photograph had about it an expressive authority that seemed to fit the subject better than the smooth, plastic description of the classical fine print”.

Mandou bem Szarkowski…

Word-photography pairing

Inspired by an article written by Geoff Dyer called ‘form: word + photography’ and published by Zum magazine in May 2014, I found resonance for an aspect of great relevance for me in photography that is ‘marriage of the word with the photograph’ or ‘photography’ with the word’. For me, there is often an exchange of roles, i.e., who was born first, like the story: ‘the egg or the chicken?’: ‘The word or the photo?’.

Dyer cites some books that historically fall into this category and after reading his article I was tempted to buy one and ended up buying the ‘Looking at photographs’ where John Szarkowski ‘houses’ 100 photographs from the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York ( the most iconic in his perspective in 1973, of course) with ‘words’ about such photos. Despite having the book in my hands for less than 24 hours, I was able to perceive real jewels – both ‘jewels-words’ and ‘jewels-photographs’ – that are in it.

One of these gems is a photo by William Klein made in Moscow in 1959 that Szarkowski’s book does not give the name (what a mistake Szarkowski!), But I know it’s a bikini because it’s the cover of a Photofile (Thames & Hudson, 2017) from Klein that I have in my small library. “Bikini” escapes – in my modest knowledge and understanding of Klein’s work – from the ‘rule’ of (almost all) photographs by this author who excels in ‘meter’ within the rectangle, a great diversity of elements of composition. ‘Bikini’ has 6 layers or beautifully defined plans …. and, many mysteries … tensions … and, poetry.

Well, among the many things that Szarkowski talks about in this photograph, I read something I want to share:

“It was recognized long ago that so-called good photographic technique did not invariably make the best picture. Sometimes the gritty, graphic simplicity of the badly made photograph had about it an expressive authority that seemed to fit the subject better than the smooth, plastic description of the classical fine print ”.

You did well Szarkowski!!! …

Let us now praise the famous men and women of the countryside (text and photographs by antonio mozeto, são carlos, sp, brazil)

Looking carefully and attentively at these two portraits, I see a small passage in my head containing great words by James Agee when he says to whom his (great) book “Let us now praise famous men” (*) (Cia das Letras. Translation by Caetano W. 2009. James Agee and legendary photos of Walker Evans) had been written:

… “In any case, this is a book about ‘sharecroppers’, and it is written for all those who have a weakness in their hearts for the laughter and tears inherent in poverty seen from afar, and especially for …”enjoy a little better and more guilty the next good meal you have ”(page 31).

My message here is simply this: many of us do not realize the hard daily work of a rural worker in the production of food that reaches the tables of our families in Brazil and even many around the world. This is also true for the production of commodities that are mostly exported.

(*) book (journalist, poet and writer James Rufus Agee) and photographs (photographer Walker Evans) generated in the period of June-August 1936 when both worked on the production of a report (which in fact NEVER came to be published in the press) in Alabana state, USA, in order to portray the effects of the devastating period of the Great Depression. They even lived with three ‘meeiros’ families, establishing a very close relationship with several people.

Both the book and the photographs translate well this degree of involvement given the emotion and the level of detail with which Agee describes people, houses, their rooms and belongings. Evans’ photographs corroborate everything Agee writes, and even add even more emotion.

In short: “Evans’ photographs are, for me, the natural visual lexicon of Agee’s delightful descriptions. Sensations, the spirit of places and objects spontaneously spill out of Evans’ images ”.

The power of photography: time, ephemerality and memory

Oh !, time … time, that damn-blessed inexorable variable … inevitable, unshakable, inflexible, relentless, unspeakable variable … the time that denies everything and erases everything … the time that yellow the love letter leaf kept so long in a drawer … forgotten there, but not from time, to time … time that wears out love … time that soothes passions and brings loneliness … time for a utopian world … and, at the same time, a dystopian world … time that everything weathered and destroyed the beauty and perfection of the beautiful … that appeased, that ended wars … that ended everything, from manias to epidemics and pandemics, that calmed the gusts … that the flower withers, rots the fruit and soothes the pain … which creates unrest and brings fear … Continue reading “The power of photography: time, ephemerality and memory”

***shyness***

****shyness******street_photography_2018***

mon amazone pittoresque

Nostalgic and bucolic colors of the old and good color films.

COVID-19 times have been tough but have provided me with an opportunity, with time and patience, to scan old negatives and color slides that I used so much in my film photography. And, I rediscovered the beauty of the nostalgic and bucolic colors that these films (I used regular 100-200 ASA films from Kodak and Fuji) reproduced. Continue reading “Nostalgic and bucolic colors of the old and good color films.”

What touches me most in the photos of a young man of just 17 years old named Stanley Kubrick.

I write this post not based on deep knowledge about Kubrick’s work because I am far from having it, but much more guided by my admiration for the work of this great artist and the emotion that his photos make me feel.

Continue reading “What touches me most in the photos of a young man of just 17 years old named Stanley Kubrick.”

![[.P.O.R.T.R.A.I.T.S.]](https://antoniomozetophotography.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/pag-dupla-extra-rurais-07-.jpg?w=924&h=0&crop=1)

![[dis-words]](https://antoniomozetophotography.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/dsc_9019b.jpg?w=924&h=0&crop=1)